Introduction

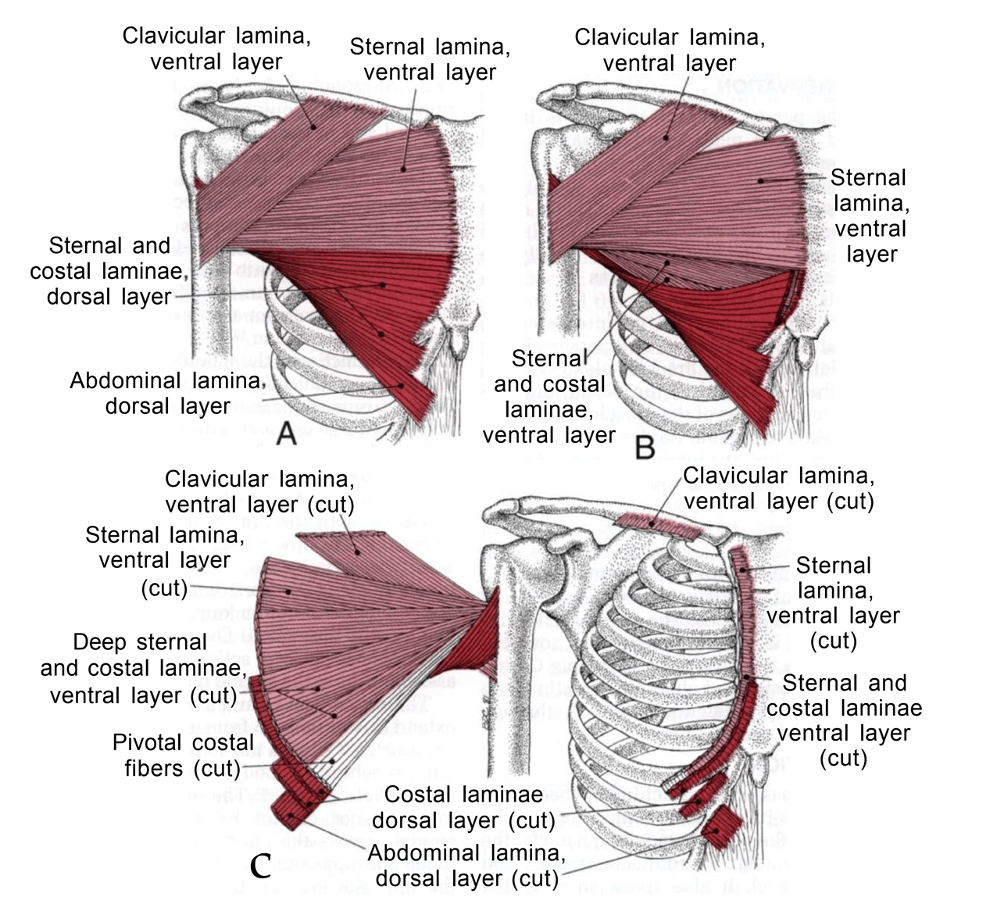

“Pectoralis” comes from pectus, Latin for “breast.” “Major” means it’s the largest of the four pectoral muscles. The pectoralis major is a fan shaped large, thick, and flat muscle of the pectoral girdle of the upper limb. In both men and women, this muscle make up the muscular portion of the breasts.(1,2) This muscle consists of multiple overlapping laminae in a playing-card arrangement.(3)

Anatomy

Origin

Even though there are different opinions on different anatomy books about the arrangement of the lowest fibers of the pectoralis major muscle, they generally agree that the fibers of the entire muscle attach mediallyas four separate sections: (1) clavicular fibers to the clavicle, (2) sternal fibers to the sternum, (3) costal fibers to the cartilages of the second to sixth or seventh ribs, and (4) abdominal fibers to the superficial aponeuroses of the obliquus externus abdominis, and occasionally to the rectus abdominis muscle.(3)

Insertion

The muscle runs obliquely and horizontally across the chest to terminate on the greater tubercle of the humerus comprising two layers, a ventral and a dorsal.(3,4)

Action

All sections of the pectoralis major muscle contract together during strong adduction of the arm assisted by the teres major and minor, the anterior and posterior deltoid, the subscapularis, and the long head of the triceps muscles.(3)

Functionally the different sections of the muscle may play an independent role and participate in diverse movements. The clavicular portion synergistically with clavicular part of the deltoid adducts and elevates the arm. It brings the upper arm back from external rotation to the neutral position. Other low range of motion with the elevation of the arm includes touching the chin. The sternoclavicular portion mostly adducts the arm with internal rotation.

The abdominal portion contributes to depression of the shoulder and it supports push-up movements in the neutral position.(2)

Innervation

Lateral pectoral nerves from the spinal nerves C5 supplies the clavicular and sternal sections of the pectoralis major muscle, while the medial pectoral nerve arises from spinal nerves C8 and T1 supply the caudal third, the costal, and abdominal sections of the muscle.(3)

Trigger points and Pain Pattern

The pectoralis major muscle is likely to develop trigger points (TrPs) in five areas, each with a distinctive pain reference pattern. Pain and tenderness are referred unilaterally. The TrPs located in the clavicular sectionrefer pain over the anterior deltoid muscle and locally to the clavicular section of the pectoralis major itself.

Active TrPs in the intermediate sternal sectionof the pectoralis major are likely to refer intense pain to the anterior chest and down the inner aspect of the arm. If sufficiently active, these TrPs refer pain also to the volar aspect of the forearm and ulnar side of the hand.

Active TrPs located in the medial sternal sectionof the pectoralis major refer pain locally and over the sternum without crossing the midline. In the costal and abdominal sectionof the pectoralis major, TrPs develop in two pectoral regions. One of these regions lies along the lateral border of the muscle.

These border TrPs cause breast tenderness with hypersensitivity of the nipple, intolerance to clothing, and often breast pain. More medially, a TrP associated with somatovisceral cardiac arrhythmias is located on the right side between the fifth and sixth ribs, just below the point where the lower border of the fifth rib crosses a vertical line that lies midway between the margin of the sternum and the nipple.

The spot tenderness of this TrP is associated with ectopic cardiac rhythms, but not with any pain complaint.(3)

Satellite trigger points include the anterior deltoid, sternocleidomastoid, scalenes, trapezius, rhomboids.(5)

Perpetuation of Trigger Points

Pectoralis major TrPs can be activated and perpetuated by activities that can produces sustained shortening of the pectoral muscles forming a round-shouldered posture.

These activities include prolonged sitting, reading and writing, and standing with a slouched. The TrPs may also be initiated in other ways including heavy lifting (especially when reaching out in front), by overuse of arm adduction, by sustained lifting in a fixed position, by immobilization of the arm in the adducted position, by sustained high levels of anxiety, or by exposure of fatigued muscles to cold air.(3)

References

1. Claire Davies AD. The Trigger Point Therapy Workbook- Your Self-Treatment Guide for Pain Relief. 2013.

2. Larionov A, Yotovski P, Filgueira L. A Detailed Review on the Clinical Anatomy of the Pectoralis Major Muscle. SM J Clin Anat. 2018;2(3):1015.

3. DAVID G. SIMONS, JANET G. TRAVELL LSS. Travell & Simons’ myofascial pain and dysfunction – the trigger point manual Volume 1. 2nd editio. 1999.

4. Finando D, Ac L. Trigger Point Self-Care Manual- For Pain-Free Movement. Inner Traditions / Bear & Company; 2005.

5. Finando D, Finando S. Trigger Point Therapy for Myofascial Pain. 2005.

MD, PhD. Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation Physician from São Paulo - Brazil. Pain Fellowship in University of São Paulo.